Zersen Family History

Zersen Family History

PREFACE

This family history has been in process for over forty years. It began when I first visited Germany in 1960 and developed in the years when I studied in Germany in the mid 1960s. Countless pieces of information along with pictures were placed in files during all the years when I never had the time to organize and analyze it. Finally, the time came to put it all together.

The Zersen story seems most fascinating with respect to aspects that are new and surprising to us. The contemporary details with which many of us are familiar may seem unimportant. However, future generations of this family will find our stories as interesting to them as we have found those of our ancestors. For that reason, it’s important to compile the information now before we have forgotten it—or we ourselves are forgotten.

The history takes us back in the U.S. Zersen family six generations to the time when Carl Ludwig Zersen immigrated to America. However, we can now count 12 generations to the time when Cord Zersen, earliest known ancestor, lived in Hamelspringe, Germany.

The exciting thing about this history is that as a result of the research done in Germany and in the United States during the last few years we can say with certainty that all living Zersens/Zerssens in the United States and in Germany are related to one another. This story, therefore, is not generalized history. If your name is Zersen/Zerssen or you are related to any Zersens/Zerssens, this is your story.

ZERSEN FAMILY HISTORY

Some may consider it insignificant to be a part of such a small number of families worldwide. However, in many ways it’s fascinating that this small group of people has been able to rediscover itself and to learn about the significant impact that its families have had historically as well as today.

If one checks the International White Pages online (telephone directories), there are 11 Zersen family units in Germany and 3 more with the double “s” spelling. There are 5 family units with the von Zerssen spelling. In the United States, there are 35 family units with the Zersen spelling and none with other spellings.

Of course, some Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens may not have telephone listings. In general, however, one might surmise from the total listings in international telephone directories, given that some listings are for singles and others for multiple family members, that worldwide, there are not more than 150 people with the name.

Some who were born as Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens had their names changed in marriage and others are children or descendents in a family where the mother’s maiden name was Zersen/Zerssen/von Zerssen. In terms of names, this is a very small cluster of surnames.

Should this be interesting to anyone? There are a number of things that may be surprising. In the first place, the Zersen name is a very ancient name, one of a few the meaning of which has been studied by historians and students of names. Secondly, the geographic homeland of the Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens is unique and has experienced significant moments in history worth retelling. Finally, although the Zersen/Zerssen/von Zerssen family has a history as old as 1000 years, it has just rediscovered itself during the last 40 years.

Contacts continue to be made to establish relationships between the various branches of those bearing the surname. Forty members of the extended family with the Zersen spelling met for the first time from both sides of the Atlantic in Colorado in July of 2008. And a larger gathering of all Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens is proposed at the Pappmuehle (below) in Zersen, Germany, in 2011.

THE HISTORY OF THE ZERSEN NAME

Once upon a time, as all good stories begin, there were no last names or family names. In Germany, the year 1200 AD is typically given as the beginning for the use of such names. Prior to this, people were known in their scattered villages by personal names and by a house sign of the family’s choice. As larger cities were established after 1200, and people moved to these cities, it became necessary to distinguish between people with the same personal names. By 1500, it was necessary for people to have family names so they could be identified on tax rolls. They came to be characterized by old German or Christian derivations, their place of origin, their line of work and, sometimes, even by descriptions of how they looked to others. From old German personal names like Eberhardt came family names like Ebert, Ebel and Ebeling. From Christian names like Andreas came Drewes and Reese. From towns came names like Oldendorf and Zersen. From occupations, names like Schmied, Mueller and Schneider. Some named themselves after the symbol on their house signs (Wulf, Vogel, Rose or Kettelhake—the symbol of the hook in the fireplace on which the kettle hangs while cooking). Some were named after professions like Meyer/Meier (person responsible for some land), Ritter (knight), Richter (judge) and Pieper (town flautist!). Finally, some took names from characteristics like Kluge (wise), Schwarzbart (black beard) and Hardekop (hard headed).

All this is important background in order to understand the prevailing theories for the name Zersen as a family name. One theory assumes that the name occurred as a family name in the 1200s when people moving to the cities or taking on roles of responsibility for local nobility chose to designate themselves by their place of origin. Those who were in the employ of the Duke of the local castle Schaumburg could pass on their roles and status to their children. Whole generations passed on these entitlements typically designated as a status permitting the use of the word “von.” So it happened, according to this theory, that a person from Zersen who worked for the Duke could be known as Hubertus von Zersen, etc. His descendents would then keep this place name as a surname. Those who did not work for nobility and become land-owners also used the town name as their family name, but written simply as, e.g., Friedrich Zersen.

Of course, nothing is as simple as it seems, so there are two addenda to such a theory. First, there is the matter of spelling. Since average people could not read and write in medieval times, Zersen came to be spelled in whatever way the person who was writing thought it sounded. Many are the spellings which occur: They include Zersen, Ziersne, Zersne, Cersne, Certzen, Czerssen, Tzerssne, Tzersen, Tzertzen, Tsertzen, Zertschen, Zertze, Sertzen, Serssen, Cirttzin, along with others even more surprising. Thus, historically there were many spellings of the name. For a variety of reasons, those with the “von” before their name tended to spell it with a double “s,” as in Zerssen (although there were exceptions). Other families without the “von” used either the double or single “s.” In the United States, because all Zersens are descended from one immigrant, Carl Ludwig Zersen, all families use the single “s” spelling. (However, see Postscript.)

The second addendum concerns the meaning of the name itself. There are at least four such theories. One proposed by Friedrich Koelling is that the name Zersen goes back to a personal name that is no longer in use. He suggests that the common “hausen” formula, meaning “house of,” could have been attached to a name like Tser or Tseyro. He cites many villages in the Suentel/Deister mountain area that have similar orthographic possibilities: Wiersen, house of Wigbald, Haddesen, house of Haddo, and Barksen, house of Bark or Berk. Those who know Scandinavian family names can pose similar comparisons with names like Jens, Sven and Harold (Jensen/Jenson, Svenson/Swensen, Haroldson, etc.). The theory, then, is that Zersen is a form of Tsersen, the House of Tser, a prominent man who lived at least 800 years ago and around whom a group of houses developed which took on village status.

The second theory relates the name to the serrated element in the pothook of the von Zerssen coat of arms. The German word that described this process of pulling one iron element into place along the coordinate beam is “zerreisen,” to pull iron. It has been suggested that the Zersen name comes from this verb.

A third theory is that after the famous battle with the forces of Charlemagne along the slopes below the Hohenstein in 872, local tribesman who survived the battle named the village they established there after the brook where so many of their compatriots lost their lives. The supposition of this theory is that the current name for the brook, Blutbach, (see left) in a predecessor language, was a form of the word “Zersen.”

A third theory is that after the famous battle with the forces of Charlemagne along the slopes below the Hohenstein in 872, local tribesman who survived the battle named the village they established there after the brook where so many of their compatriots lost their lives. The supposition of this theory is that the current name for the brook, Blutbach, (see left) in a predecessor language, was a form of the word “Zersen.”

Most recently, both the von Zerssen and the Zersen families worked with the Namenberatungsstelle (Office for the Study of Names) at the University of Leipzig. Their 13-page report (found on the zersen.net website at the tab Zersen Name (Deutsch) written in June of 2008 rejected all three theories and advanced a fourth. When the Romans came to Germany, they brought with them cherry seeds to produce cherry trees. In Latin, the word for cherry tree, many of which were planted in northern Germany, is ceresia. This word was given to a Hof (farm) or settlement, and the word evolved orthographically into the present day Zersen.

As in all historical theories, the reader has to make choices. No matter which theory one chooses, however, the name Zersen is at least either 800 or 2000 years old, one of the oldest names in Germany. Of course, family history cannot be traced back this far, but the name itself is of ancient origin. When people ask, “What kind of a name is that? Is it German?” one can only smile, knowing there is no way to answer that question without giving a history lesson. This name pre-dates Germany that became a nation in 1848. It predates Otto I who became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 936. It goes back to wild, primitive times in central Europe when there were no organized communities. It reverts to a time of tribesmen and open fires with kettles. The name is very special.

POSTSCRIPT ON LANGUAGE USAGE

It is interesting to add an postscript, just to increase the awe that language creates. On Dec. 25, 1904 (Christmas present to America), Marcin Zersen arrived on the ship Patricia from Hamburg. He carried a Polish passport! Forty Szersens have emigrated to the U.S. from Hungary (e.g., Istvan Szerszen and Ivan Szersen), from Jugoslavia, Austria, Norway and Denmark. 37 Szerszens emigrated from Galicia (now Poland and Austria) and Austria. Five Serszens emigrated from Hungary and Galicia. A Hungarian academic friend of mine in Budapest tells me that Szersen is still common in Hungary today. What kind of names are these and are they linguistically related to Cersne and Zersen? Some years ago when I lived in Chicago, there was a radio disc jockey by the name of Connie Szersen. I asked her about her ancestry and she told me that she had always heard it was Polish. There is also a suburb of Warsaw with the name Zerzen.

Interesting as such comparisons are, it may be best to regard such spellings as the results of attaching letters to sounds in different linguistic environments (phonetic development). For example, Szersen in Polish, e.g., is “hornet.” To assume that there is a dependency of the German on the Slavic or even ultimately the Sanskrit may not be demonstrable. We may never know the final answer, but it is worth keeping an open mind about the contributions of linguistic heritage.

View of Zersen and the Weser River Valley from the top of the Hohenstein

THE GEOGRAPHIC AND HISTORIC HOMELAND OF THE ZERSENS

To understand that all people with the name Zersen have something in common besides the name, one has to understand that all of us also came from the same place. Over the centuries, people with the name Zersen moved to other villages and cities in Germany, but all had their beginnings in Cersne/Zersen. (GFN, 12)

Today, Zersen is a village of 400 people that is incorporated as part of the larger community of Hessich-Oldendorf. It is about 45 minutes from the city of Hanover, lying in the Suentel Mountain range. A lovely village of red-brick homes and farms, it is dominated by a 1000 foot cliff wall, the Hohenstein, which rises above the village, giving a view to the Weser River hill country (Weserbergland) for miles in every direction.

The Hohenstein is geologically significant because it is the highest point in north- central Germany. From here, the mountainous terrain descends toward the increasingly flat surfaces surrounding Hanover, Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein.

Peak of the Hohenstein

Over the course of history, many significant events took place in this area. Among the few which can still be recounted, and are worth remembering as a part of our common heritage, are three wars.

The significant heights of the cliff (about 100 feet), jutting up precipitously from the surrounding countryside, made it a symbol of awe, and therefore a place of worship, for the ancient people. How far back such traditions went cannot be said. During Charlemagne’s reign, a major battle took place at this spot (872) because of its significance as a pagan shrine. A sanctuary (Gruene Altar) is still shown upon the summit next to which were found artifacts from sacrifices that are now in the museum at the University in Marburg.

Ancient Beech tree on the Dachtefeld

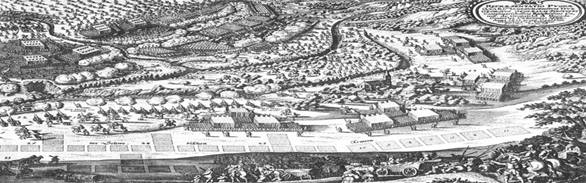

Merian etching of the battle between Hessisch Oldendorf and Fischbeck in 1633

Another memorable event taking place here 761 years later was also a battle, this time during the Thirty Year War, known as The Slaughter at Hessisch-Oldendorf, June 28, 1633. In a well-known Merian etching of this event, one can see all the troops lined up for battle, set within the spectrum of surrounding towns, Zersen being on the far right end. Once again it is a battle to attempt to enforce religious claims on the Zersens (and, of course, their neighbors in the larger world). Since 1559, the Zersens had been Lutheran. Seventy-one years later, during the Counter-Reformation, there was an attempt to re-claim the cloisters, churches and hospices for Roman Catholicism. However, in 1630, King Gustav Adolph of Lutheran Sweden decided to challenge the growing claim of Catholicism (or to state it politically, the growing claim of the Spanish Hapsburg dynasty). Although the King is killed in battle in 1633, the war rages on in Lower Saxony under Duke George and comes to a climax with a Protestant victory. A first hand report of the battle was provided by Tonnies von Zersen of Echtringhausen. He writes that he kept 100 horses quartered for military use. The victory on June 28 assured that the region remained Lutheran to this day.

A final major event, also a battle, took place in this area during WWII. On April 3-4, 1945, the American 5th Armored Division crossed the Rhine River at Wesel, and moved rapidly forward, addressing resistance, toward the Weser River. The division crossed at Hamlin on April 9, 1945 as the 407th Infantry was engaged to begin clearing the Obernkirchen region east of the Weser. After clearing German opposition in the Suentel Mountains with the fall of Wilsede and Hessisch-Oldendorf on April 12, 1945, the division advanced toward the Elbe River against little or no opposition. This led to a major victory in the area that helped establish the outcome of the war. During the battles, many local houses were destroyed, and the roof of the Zersen homestead was burned-off by shellfire.

One has to pause to reflect on the number of Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens who were killed in these and other battles over the years. It is easy to identify their names on monuments from the First and Second World Wars in local cemeteries. (In Haddessen, for example, one can read the names of Gustav Zersen and others who were killed.) The smaller numbers of those families with these surnames in Germany today has a direct relationship to the losses suffered in local battles as well as on the Russian front during World War II.

One has to pause to reflect on the number of Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens who were killed in these and other battles over the years. It is easy to identify their names on monuments from the First and Second World Wars in local cemeteries. (In Haddessen, for example, one can read the names of Gustav Zersen and others who were killed.) The smaller numbers of those families with these surnames in Germany today has a direct relationship to the losses suffered in local battles as well as on the Russian front during World War II. Among other more personal and diminutive aspects of the geography and history which make this place a personal homeland for people of Zersen/Zerssen/von Zerssen ancestry are biographies of Zersen notables, stories and legends from the area around the village of Zersen, visual symbols in buildings and the story of the von Zerssen coat of arms.

There are many biographies of Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens who were knights, poets, pastors, scholars, monks and good citizens. Their stories will have to be told by others interested in the research, but the study will not be fruitless because there were more people with these surnames 700 years ago than there are today. One interesting story is worth telling, however. In the Bueckeburg Niedersaechsisches Staatsarchiv (Kartenabteilung 200/s pk.), one can find an interesting defamatory letter (Schmaehbrief) written on Nov. 30, 1523 by Thonnies von Wettbergen against the knights Borchert von Landsberg and Wulfert von Zersen. He complains that because they refuse to pay a debt, he would like to have them hung or flogged to death on a wheel (both of them deaths unworthy of a knight). He draws pictures of them under such conditions in his letter that is a traditional form of castigation at that time. One can thus see that Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens were not always the most exemplary citizens!

A booklet of the folktales from the area around Zersen and the Hohenstein (high cliff) has been published in German and is available for those who want to know the legends of their ancestors. Among the tales in Heimat Sagen (Fables from the Homeland) are the following:

The Treasure at the Hohenstein At the top of the southeast side of the high cliff (Hohenstein) lies a prominent boulder emerging from the ground. It is called either the “green altar,” “pagan altar,” “sacrificial altar” or “pulpit.” On this stone, our ancestors brought their sacrifices to Donner, god of thunder, when they were still pagans. On one rock next to the “green altar,” a mysterious writing appears every seven years on St. John’s Day (June 21). It is visible for 24 hours and at night it is fire-red. Our fathers and grandfathers were still able to see it, but no human has ever been able to read it or make sense of it. Wise people say that anyone who is able to read it will become a very rich person-- for the script explains where there is a great treasure hidden in a cave of the Hohenstein which is guarded day and night by a Black Spirit.

The Founding of the Great Church at Fischbeck (church home of the Haddssen Zersens where immigrant, Carl Ludwig Zersen, was baptized and confirmed): In ancient times, a knight by the name of Rickbert lived on the heights of the Suentel Mountains with his lovely, pious wife, Helmberg. As the Count returned from fighting the Huns, he became very sick. His wife had received a remarkable potion brought by a pilgrim from the Holy Land and she gave it to her husband to drink. He had hardly tasted it when he incurred terrible pains. He thought that Helmburg had poisoned him and therefore he wanted to kill her with his sword. However, he fell into a deep sleep and never carried out his intent. After many hours he awoke. The illness had disappeared, but his suspicions against his wife were still there. Helmburg begged him to prove her innocence through a test of fire. Therefore, a huge fire was built in an open area. Two times his wife managed to get through the dancing flames. The third time a burning ember fell upon her bare arm. That led the knight to suspect her guilt, and he condemned her to death. However, this was not to be death by the sword. She would be placed with her servant upon a wagon pulled by four unbridled horses. The wild ride took them down the mountain from the castle, over rocks and through deep gullies, right into thorn patches and treacherous swamps. It was a miracle that the wagon didn’t fall apart. Finally, the foam-covered horses came to a stop at a stream in a meadow. The countess had remained unhurt after this terrible ride. Exhausted, she bent down to the brook to quench her burning thirst. As she dipped her hand in the water, she caught a little fish. In thanks for her miraculous salvation, Helmburg built a cloister on the spot where the horses had stopped, and she called it Fischbeck (“fish pond”). She continued to live in this cloister and led a quiet and retired life. (The cloister she founded remains a Lutheran cloister to this day and provides accommodations for pilgrims.)

In churches like the great Cathedral in Naumburg there is a stained glass window commemorating the Cersne family. In the Castle Church in Bueckeburg there is an oil painting of one of its early Lutheran pastors with the name Zerssen. In the oldest gothic church in Germany, St. Elizabeth’s in Marburg, there is a grave plate in the floor for the knight named Zerssen. The name is also found in St. Michael’s in Hildesheim. In the Lutheran church in Oldendorf there is a stone carving of the Kesselhaken (pot hook) which serves as the center of the von Zerssen coat of arms.

This coat of arms is one of the oldest Wappen in Germany. It shows a pot-hook (typically placed in open fireplaces where huge iron cauldrons would hang) surmounted by the head of a cock. It has been suggested that it may have been used as a brand for cattle as well. The first written reference to this unique traditional symbol goes back to 1328 and numerous examples can be found in European books of heraldry. By contrast, it should be said that the coats of arms sent through the mail by heraldic companies trying to sell merchandise in the U.S. are sheer concoctions and have nothing to do with the Zersen name. Interestingly, in terms of the history of the name, this unique pot-hook symbol is found on coats of arms from Zerssens in Hanover, Zerssens in Hamburg, Bremen and Luebeck, Zerssens in Prussia and Zertschens in Braunschweig. There are many different styles, but the black pothook is always featured with a red-crowned rooster’s head encircled by silver plumage.

THE RE-DISCOVERY OF THE ZERSEN FAMILY HERITAGE

What little has been told so far is information learned in the past 40 years. However, ongoing research brings new insights and discoveries with each passing year. The story of how this sleuthing took place is interesting in itself and may inspire other members of the Zersen family in America or Germany to pursue ongoing study in family history.

In 1960, as the author of this article prepared to accompany his best friend and future brother-in-law, Carl Uebel, on a visit to Germany, he took with him recently-gleaned information from the Uncle (Oskar Wachler of Molzen, Germany) of his aunt, Ruth Michael Zersen. Wachler had followed up on a family belief in America that somewhere there was a town called Zersen. He wrote that he had visited the town and gave directions on how to find it. (This was in a day before internet searches and frequent travel could have simplified such a quest.)

With nothing but Wachler’s directions, the two young men visited Zersen in July of 1960 and asked at a Gasthaus if any Zersens lived in the village. The Innkeeper gave the boys an address for a retired school teacher, Friedrich Koelling, in neighboring Hessisch-Oldendorf, and David gave this address to his father upon returning home. Carl Zersen began a correspondence with Koelling, and with a man Koelling recommend, Hans-Wulfert von Zerssen, which lasted several years. Because of his personal interest in genealogical research, Koelling did research in church records and sent information documenting the American family’s ties with ancestors in Germany.

In spring of 1964, David Zersen returned to Germany to study at the University of Goettingen. In October, when he felt somewhat confident of his ability in German, he visited Anna Zersen who lived one block from Friedrich Koelling. She went to her kitchen cupboard and brought a letter that the family had saved for 40 years in the hopes that some day someone might come back to Germany from America. They thought perhaps during WWII a soldier might come, but no one ever came. As the letter was read, Anna Zersen regularly asked about the contents, “Stimmt das, stimmt das”? (“does it make sense?”) The letter was written in 1921 at the close of the WWI and made references to the writer’s children, the twins, Rudolph and Adolph. It became clear to me that this was a letter from my grandfather, Frederick, to his family in Germany—and that I was related to this Anna in whose kitchen I sat! In the letter from 1921, now in the possession of Juergen Zersen, grandson of Anna, in Hanover, Germany, Frederick Zersen writes in old German script that he and his four brothers (Heinrich, Wilhelm, Herman and Adolph) collected approximately $1500 at the end of WWI to send to their cousins in Haddessen and East Friesland. This letter became the key to finding members of this Zersen family in Germany and reuniting them to relatives in the United States.

Many years have now passed and some of the original people in the story have since died: Friedrich Koelling, Anna Zersen and her daughter-in-law Marie Zersen, all in Oldendorf, and Martha Zersen and Ferdi Wache in Haddessen. However, other family members still live on and numerous visits from family in America over the years have kept the initial contacts alive. Edith Zersen Wache, her children, Norbert and Gudrun Hermann (spouse Peter and daughter Corinna), and nephew Juergen and niece Karin Zersen Stoltmann (and their spouses, Petra and Bernd) have been known to us now for 44 years.

In the summer of 2003, two very interesting things happened. David Zersen had written letters to 23 Zersens found in the Internet International White Pages of Germany. Only three responded. On June 3, Theodore Zersen and his son, Rolf, and their wives, Harmana and Hannelore from East Friesland (near the Dutch border) visited with David Zersen in the village of Farven. They read together the 1921 letter from Frederick Zersen—and it was noticed for the first time-- that money had also been sent to a cousin in East Friesland. These visitors were therefore also directly related.

The other two families that responded to the email inquiry were Herbert and Lotte Zersen from Obernkirchen and Guenter Zersen and Heinrich and Liselotte Zersen in Barksen. Subsequent visits to both of these families demonstrated their direct relationship.

On the last day of David Zersen’s 2003 visit in Haddessen, he showed a 1929 picture of the birthplace of immigrant Carl Ludwig to Edith Zersen Wache’s husband, Ferdi. Ferdi looked at the photo and said, “sicher, das Haus steht noch” (that house is still standing).We took the photo and walked a couple streets to find it. There was House 24, built by the Great-great grandfather, Friedrich Wilhelm Zersen in 1824, and in which his son, Carl Ludwig, was born in 1832. It’s a beautiful, very large Fachwerk (Tudor style) building formed with crossed beams and plaster-covered centers. The two boys playing in the front yard made me feel like I had come home.

A reciprocal German/American family connection took place when Juergen Zersen and his wife Petra attended the Zersen family reunion in Bellingham, Washington in 2003. Subsequently, Petra and Juergen returned in 2008 along with his sister, Karin, and husband, Bernd Stoltmann for a Zersen reunion in Estes Park, Colorado. The 2003 visit was the first time in 146 years, since Carl Ludwig’s immigration to America, that members of the Zersen family from Germany crossed the Atlantic to visit relatives in America!

With this serendipitous and personal account of how it happened that one branch of the Zersen family in both Germany and America came to know each other again, it can now be told what they came to learn about each other. The details of the immigration and settlement in the United States were learned from careful research performed over the last forty years. The story is here told in brief. Genealogical descent charts (on zersen.net at the Descendancy Charts tab) took many years to develop because many aspects of the family relationships were never clear. As it was with the Rosetta stone that helped Champollion to decipher the ancient hieroglyphs, so it was with the 1921 letter that after many readings finally gave the key to the connections in the relationship. Without this letter preserved by Anna Zersen in the Hessisch-Oldendorf kitchen cupboard, Zersens in America and Germany would never have found each other again.

Research provided by Dr. Syliva Moehle of Goettingen helped to establish some of the relationships that were unclear. As a result of this research, a direct line can now be established between all Zersens in German and the United States and their common ancestor, Cord Zersen, born in Hammelspringe in 1623.

One branch of the family which uses the German Doppel “S” in the spelling has also been connected to the family.

Remaining to be deciphered is the point at which the Zersens/Zerssens left the village of Zersen and, hence, their relationships with other Zersens now known as the von Zerssen family. Current historical research continues along with the prospect of DNA research.

Hamelspringe, first known home of the Zersens

LIFE IN HAMELSPRINGE AND HADDESSEN

As just stated, all Zersens/Zerssens/von Zerssens left the village of Zersen at some point centuries ago. Reasons for their departure are not clear because written records from the earlier centuries are not available. New people settled in Zersen, and the Zersens moved out to many other villages and cities. In the case of the family line to which the American Zersens belong, family members left Zersen for a neighboring village of Hamelspringe (at some point in the 1500s). Members of the von Zerssen family are able to document their departure from the village with more clarity. What follows will be an attempt to use historical records to describe what can be known of the Zersen/Zerssen family who parents owned a Hof (farmstead) in Hamelspringe in the late 1500s. Both parents died leaving their farm in Hamelspringe to their eldest son, Cord. It is from Cord that all living Zersens/Zerssens in Europe and America are descended.

Cord (an early form of Kurt) Zersen was born in 1623. His father died and his mother married again. Then his mother died, and his step-father married again. Cord was the heir of the farm on which his stepparents continued to live. He married Agnese Hoffemeister and had a son, Johann. Agnese died and Cord married again, this time to Ilsabeth Hoppe. His son, Johann, followed him in the main house and Cord and his wife probably then moved into separate rooms reserved for the parents/grandparents, the custom of the time. Johann and his wife, Ilsa Catharina Nagels, had nine children, the eldest of whom was Hans Hinrich.

Hans Hinrich, inherited the homstead, married Engel Elisebeth Niemeyer and took over the farm. It was then his responsibility to care for his parents in rooms in the homestead, Johann and Ilsa, in the large family home.

Hans’ and Engel’s eldest son was Hans Christian. Upon his marriage to Sophie Katz, he inherited the farm, and moved into the main house. 1734, he built a separate retirement (Leibzucht) home for his parents.

In September of 2008, Juergen Zersen and David Zersen went to Hamelspringe to see if anything could be learned about these ancestors. It is probably true that another home built in the 1800s has replaced the main home, in which Cord, his eldest son and eldest grandson lived. Research is being conducted to determine the age of the current house #4.

However, the two cousins did find the 1734 retirement (Leibzuecht) home of Hans Hinrich and Engel Elisebeth Zertzen. Their names are carved above the door and a gracious widower who lives there now invited us inside to see the lovely, renovated interior.

Hans Christian and Sophie had five children, the eldest of whom was Johann Heinrich. He was born in Hamelspringe in 1777 (one year after the American Revolution). He grew to manhood, fell in love with and married Dorothee Louise Krueckeberg who was born in neighboring Bensen on Feb. 4, 1778. Her father was the village blacksmith and he had roots in Bensen going back to 1719 when he was born there. The young couple probably accepted an invitation from Dorothee’s parents to live with them, and there Johan set up a loom to ply his trade as a linen weaver. The industrial revolution came late to the backwoods areas of north-central Germany. People set up looms in their homes, providing a substantial cottage industry in an otherwise agricultural area.

Fishbeck crypt from the 12th Century

Johann and Dorothee had two children born in Bensen, Friedrich Wilhelm, Jan. 26, 1799, and Sophie Wilhelmine Justine, born Feb. 4, 1801. At some point the couple moved to Haddessen because their next two children, Ernst Christian and Carl August, were born in Haddessen, respectively, on Jan. 3, 1803 and on Feb. 19, 1805, Alll were baptized at the great Romanesque church in Fischbeck to which Bensen and Haddessen belonged. The family apparently managed an acceptable life until tragedy struck on May 6, 1805. Dorothee died at the age of 27, leaving four motherless children. Six months later, Johann was married again, this time to a woman from neighboring Hoefingen, Dorothee Sophie Hensing. The couple had two children, Johann Conrad, born Oct. 9, 1806, and Sophie Caroline Charlotte, born July 3, 1812.

Sophie’s descendents live on today in the Heinrich and Guenther Zersen families in Bakede and other nearby towns. Another descendent from this family, Herbert Zersen, lives in Obernkirchen.

When Friedrich Wilhelm had grown to manhood, at the age of 22, he married a girl from the neighboring village of Bakede, just across the mountain from Haddessen. The daughter of Ludwig Priesmeier and Dorothea Wendt, Charlotte was a young woman whose strength would be needed to hold the family together. After their marriage, Friedrich and Charlotte lived in Haddessen where Friedrich Wilhelm built House 24, homestead of all Zersens in America and many in Germany. In this home, Friedrich erected a loom and continued the weaving trade of his father.

During the fifteen years of their marriage, Friedrich and Charlotte had seven children, three sons and three daughters, all baptized at the great Romanesque church in Fischbeck. Tragedy struck the Zersen family once again when father Friedrich died at the age of 37, leaving a widow to take care of the children, two of whom were under three years of age. She was frugal and energetic and somehow managed to provide for the children. Friedrich’s father, Johann, had either been living with the family or joined them at this time. He may have supplied the family income for the next ten years by continuing his weaving trade, but on March 23,1846, he also died at the age of 69.

Charlotte remained in the homestead in Haddessen until her six children were confirmed, but around 1849 she probably moved in with one of her children outside of Haddessen, perhaps her oldest daughter. The oldest son, Heinrich Friedrich Christian, born 1822, inherited the homestead, House 24. Ernst Christian (b. 1825) and Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm (b.1829) built other homes in Haddessen. The home built by Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm (Number 34) is today the home of Edith Zersen Wache. Homes 27 and 47, also built by the Zersen brothers, are no long owned by family members. Caroline (b. 1824) married a man whose last name was Brabant, and Friederike (b. 1828) married a man named Koplin. The youngest son, Carl Ludwig, found the labor market challenging and with a friend named Tegtmeier decided to see his fortune in the United States.

An extant picture of the homestead, House 24, taken around 1929, shows a picture of Christian and his ailing wife standing in the doorway. In the foreground is the father, Heinrich Friedrich, with his grandson and a dog.

The third oldest son, Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm built House 34 in Haddessen. He also worked as a linen weaver in the home. He married Engel Dorothee Caroline Bock from Degersen. They had at least two sons, Karl Friedrich, (1865-1936), and Heinrich Friedrich Christian (1857-1924).

Founding date of Haddessen, 955 A.D.

Karl and his wife, Karoline Feldman (1874-1936) had nine children six of whom were sons, Gustav, Ferdinand, Karl, Heinrich, Fritz, and Wilhelm, The daughters and their married names were Caroline Zersen Schmidt, Minne Zersen Allekotte, and Louise Zersen Krueger. Both Gustav and Ferdinand were killed on the Russian front in WW II. Karl never married. The descendent ot Gustav is Edith Zersen Wache in Haddessen. The son of Ferdinand is Horst of Fischbeck. Fritz has a daughter, Sera Zersen Koepps. Wilhelm has two grandchildren living, Juergen Zersen of Hanover and Karin Zersen Stoltman of Berlin. All three daughters have living descendents.

PLANTING ZERSEN ROOTS IN EAST FRIESLAND

Karl Friedrich’s brother, Heinrich Friedrich (1857-1924), found it difficult to find work in Haddessen so he moved to East Friesland. There he worked for a brickyard and ultimately for the railroad in Emden. He married Tetje Uphoff (1857-1884). They had five children, Albert (1886-1924), Meta (b. 1888), Engeline (b. 1889), Karl (1890-1892), and Karl Friedrich (1892-1983).

The youngest child, Karl Friedrich married Antje Kettwich (1911-1995) and 10 children were born to them in Oldersum: Tetje (1911-1995, Gebkea (1912-1979), Heinrich (1919-1990), Anton (1922-1943), Karla (1924-), Friedrich (1927-), Garbrand (1929-), Theo (1931- ), Else (1932- ), and Adolfine (1934- ).

Hannelore Zersen and Friesland stove

Harmana Zersen at Gandersum Church

The oldest daughter, Tetja, married Hinrich Ubben, and they had 10 children, following the example of Tetja’s parents. Theo married Harmana Geerdes and they had three children, Rosemarie, Rolf and Detlef, and now nine grandchildren.

Friesland sheep heading home along dike at Zersen homestead in Gandersum

THOUGHTS TURN TO THE NEW WORLD

The story of the second-youngest son of Georg and Charlotte, Carl Ludwig, who immigrated, can be told in a bit more detail because of his impact for the Zersen family in America. He was born at 11:00 a.m. on December 7,1832 in House 24. He was baptized eight days later in the great church in Fischbeck. His godfather was Karl Ludwig Lampe of House 10 in Haddssen, and Carl Ludwig Zersen would carry on his name. The future in Germany did not look bright for young Zersen. His elder brother had inherited the homestead so there was nothing for him. Additionally, he was facing two years of military conscription in the Hanoverian army and he did not want to serve. The industrial revolution was gradually replacing the cottage industry in linen weaving, so there was no hope there. Other factors also presented a gloomy picture. Crop failures in the 1840s made food scarce, especially since the population in Schaumburg-Lippe had increased by 45% between 1795 and 1845. The situation was so difficult that between 1852 and 1859, 1500 people left the province of Schaumburg-Lippe for the New World.

In nearby, Bakede, to give an example of how it typically worked, Henry Busse,, immigrated to America to seek his fortune in 1847. (American Zersens will be interested to know that Henry Busse was also the grandfather of Sophie Kirchhoff Zersen, wife of a son of immigrant Carl Ludwig.) After a year in Sheboygan, he invited the rest of the family, his parents and four brothers and sisters, to join him. With the Busses came two of Karl Ludwig Zersen’s cousins, Fredericka and Christian Henjes, also of Bakede. Both would soon marry into the Busse family. This is how immigration happened, like the links in a chain (actually called chain immigration by sociologists), family by family.

The same story could be told about many another adventurer of the time. From the nearby town of Barksen, a man by the name of Clausing went to visit friends in the Schaumburg area near Chicago, Illinois (in those days a city of 30,000-40,000 inhabitants). He returned to Germany determined to bring his family to the New World. Karl Ludwig knew the Clausings of Barksen and heard the exciting story about farm and prairie lands, which could be purchased inexpensively. Already having relatives in the United States, he and another cousin by the name of Tegtmeier decided to join their friends, the Clausings, and sail for America. Although the only extant picture of Carl Ludwig shows him sitting down, he was remembered (as his sons would also become), a tall, strapping young man. One hundred years later, even though the Haddessen Zersens had lost all contact and knowledge of these immigrants, they still passed on the story which was handed down from one generation to the next in Germany: “Zwei grosse Maenner sind ausgewandert” (Two tall men immigrated.).”

THE FIRST ZERSEN IN THE NEW WORLD

Passage to America was booked from Bremen to New York on the America. In 1857 the Clausing family and young Tegtmeier and Zersen sailed. The crossing took six weeks and the sea was often rough. The children had to be tied down at times so they wouldn’t be thrown overboard.

The Clausing family consisted of father, mother and four children. One of the three daughters was Johanna Dorothea, born April 4, 1843. She was fourteen at the time and was to have been confirmed that year in the Lutheran Church at Dachtelfeld. Pastor Westphal had to complete his instructions quickly because of the early departure of the family. The day of departure was an emotional one, all the relatives and friends crying, convinced they would never see their loved ones again. Grandma “Hanna” later told many stories to the grandchildren over the years, keeping them spellbound with the drama of the immigration.

When the Clausings arrived, they moved to Schaumburg near Chicago, an area that had been settled by immigrants from their home province in Germany. Carl Ludwig may have stayed with the Clausings, perhaps even worked for them. In any case, three years later, wedding bells rang for a large-boned, 17 year-old, strong Johanna with flaming red hair and 28 year old Zersen. The wedding was performed by Pastor A. J. J. Franke of Zion Lutheran Church in Bensenville. It was the first wedding in the church that was later raised to build the one still standing today. The date was 1860, one year before the Civil War began.

The young husband was quite upset about this war since he had left Germany, among other reasons, to avoid serving in the military. It was possible to avoid conscription at the time by paying someone to take your place and this is what Carl Ludwig did.

At first, the newlyweds worked for a farmer near Itasca, Illinois, by the name of August Tonne, whose father himself had emigrated from Germany in 1845. After several years of saving money, the couple bought land in Russell’s Grove, Illinois upon which they built a farm and remained for almost 40 years until Carl Ludwig’s death in 1902. The name of the area changed over the years from Russell’s Grove to Fairfield to Lake Zurich. (Although the author can remember family picnics on the beach at Lake Zurich when he was a small child, it never occurred to him until this writing that that the only reason we were there with our grandparents was probably because this is where grandfather Frederick had grown up and he wanted to take us “home.”)

Here the Zersen family became parents to seven children, five sons and two daughters. Karolina and Emma died of diphtheria at the ages of two and seven, respectively. They are buried next to their parents in the Fairfield Cemetery. The sons, in order of age, Heinrich, Wilhelm, Herman, Friedrich and Theodore, grew up on the farm, all but one remaining men of the soil for most of their adult lives.

One time, as the boys were growing up, the pastor came to visit the farm and told the parents that they had five healthy sons and that it would be appropriate to give one to the Lord. Frederick was considered the least strong and perhaps also among the more gifted at learning, so the parents sent him to be educated at Concordia College in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, beginning in 1885. Theodore continued to work the farm after his marriage and until his father’s death when he sold the farm and moved to Mundelein, Illinois with his family and his mother, Johanna. Theodore worked for the railroad until his retirement. Henry moved to Nebraska where he settled as a pioneer along with his family on 160 acres of land outside of Gresham. William and Herman remained farmers in Illinois.

RELATIONSHIP TO THE VON ZERSSEN FAMILY

The von Zerssen family has a well documented history that demonstrates the heritage of three lines going back into the middle ages. Only one of these lines still exists (the Stadthager line) and it is represented by fewer than five families in the German phone directory.

In 1963, my father, Carl Zersen began a correspondence with Hans Wulfert von Zerssen, the cousin of Otto von Zerssen, the author of the book, Die Familie von Zerssen (1968). This correspondence lasted for a number of years and contacts of my own led to my meeting in 2003, Dr. Hans-Dietrich and his wife, Mrs. Gabriele von Zerssen, the son of Hans-Wulfert, at their home in Giessen. Their very cordial friendship has allowed us to learn more about their family in Germany today. Additionaly, we have developed a friendship with Dr. Detlev von Zerssen in Starnberg, Germany, and to a contact through Bill Zersen with Johannes Entz von Zerssen in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Although there is no direct demonstrable relationship between the von Zerssen families and the Zersen/Zerssen famiies, we take seriously the words of the Institute for Name Studies (Namensberatungsstelle) at the University of Leipzig. Having researched our two surname’s origin, they state: Der Familienname Zersen ist, geht man nur von der heutigen Form aus, als Herkunftsname zu erklaren, der auf dem Namen des Ortes Zersen basiert. Er bedeutet "der aus dem Ort Zersen Stammende, Kommende, Zugezogene.” (The surname Zersen…is to be understood as a place name based on the name of the village of Zersen. It means “one stemming from, coming from, tied to the village of Zersen.) In other words, all of us who bear this name, regardless of the spelling and any social distinction prescribed by title (e.g., von) have a common origin in this special place called Zersen.

In the absence of documentation prior to 1500 for our own part of the family, the commonality of our roots can be determined only with DNA testing. Such testing will not only demonstrate our common heritage, but point us together to ancient tribal roots in Eastern Europe and beyond.

POSTSCRIPT

This history is an ongoing project. As further research documents new information, this article can be revised and updated. A separate tab on the website, Current Research, provides information about studies that are either being done now or are projected.

If there is information that you know to be incorrect or if you would like to supply some new or different information, please contact me at:

Dave@Zersen.net

Many thanks go to my sister, Kathryn Uebel, for making the first attempt to collate all of this information. Individuals who had an interest in family history contributed much of the information; some of them now deceased. Among those with the greatest interest in the Zersen family in the U.S. were Helene Ming Zersen and Ann Zersen Kerbs of Mundelein, Illinois and Donald Zersen of York, Nebraska. Also Doris Hanneman, Ruth Brown and, Bill and Dave Zersen are to be thanked for paying for research that was done by Dr. Sylvia Moehle. In Germany, the personal research of Friedrich Koelling, a retired teacher in Hessisch-Oldendorf, Germany, and Hans-Wulfert von Zerssen from Kiel, Germany, was invaluable. Not insignificant was the foresight of Anna Zersen of Hessisch-Oldendorf who in 1964 offered a letter from her kitchen cabinet, which provided the lost link between the German, and American Zersen families.

Thanks also to Theo and Harmana Zersen from Gandersum, Germany, and Heinrich, Guenther and Herbert Zersen for their help. Also appreciated was the help from an old school friend, David Pope, who encouraged the use of Ancestral Quest software for the genealogy along with much advice for its application. Finally, thanks to Juergen Zersen of Hanover who joined me in Sept. of 2008 when we serendipitously discovered the actual house of our 5 great-grandparents, Hans and Engel Zertzen, built in 1734.

WORKS CONSULTED

Entz-v.Zerssen, Consul Paul H., Personal Correspondence, Letter to Carl Zersen in Santa Rosa, California, from Rendsburg, Germany, 1971.

Heimatsagen aus der Grafschaft Schaumburg. Rinteln: Verlag C. Boesendahl, 1951.

Koelling, F. Personal Correspondence, 1961, 1963.

Koelling, F. “Wie Heisst Du?” Schaumburger Lesebogen. Heimatbund der Grafschaft Schaumburg,10 Ausgabe, Maerz, 1963.

Rietstap, Illustriertes Allgemeines Wappenbuch, V & H Rolland, Band 6.

“Stift Fischbeck,” Grosse Baudenkmaeler Heft 211. Muenchen/Berlin: Deutsches Kunstverlag, 1970.

von Wettbergen, Thonnies, “Schmaebriefe auf Borchert von Landsberg und Wulfert von Zersen, 30 Nov. 1523,” Niedersaechsiches Staatsarchiv. Bueckeburg, Kartenabteilung 200.2 pk.

von Zerssen, Hanns-W., Personal Correspondence, 1971, 1981, 1983, 1983

von Zerssen, Dr. Hans-Dietrich, Personal Correspondence, July 25, 2003

von Zerssen, Otto, Die Familie von Zerssen. Rinteln: Verlag C. Boesendahl, 1968.

Zersen, Christian, Personal Correspondence, Letter to Frederick Zersen from Haus 24, Haddessen, 8 Dec. 1929.

Zersen, Friedrich, Personal Correspondence, Letter to Karl Zersen in House 34, Haddesssen, from Itasca, Illinois, July 27, 1921

Zersen, Frederick, “The Second Circuit Rider on the Soo Line,” Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly, vol. 63, no. 2, summer 1990.

Zersen, Johanna, Personal Correspondence, Letter to Friedrich Zersen from Russell’s Grove, around 1910.

Zersen, Ruth, Let The Record Be Made: Story of Gresham, Nebraska. Gresham: Historical Committee Diamond Jublilee, 1962.